…on how suppressed history breeds cycles of violence

FOREWORD

by Robert Čoban

Most tourists who visit Zanzibar know almost nothing about the horrific genocide that unfolded on these idyllic beaches in January 1964. Had Bomi Bulsara not managed to flee with his family to England that year, the world might never have heard of Freddie Mercury.

It was Saturday, 12 January. While waiting to enter one of Zanzibar’s national parks, I joined a group of locals on the terrace of a small café, watching a live broadcast of what looked like a mass display. It was Revolution Day, and the commemoration was being held at the stadium on Pemba Island, which, together with Unguja and several smaller islands, forms the Zanzibar archipelago. On the pitch, people arranged their bodies into the number 55, marking the 55th anniversary of the revolution that, on 12 January 1964, toppled Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah.

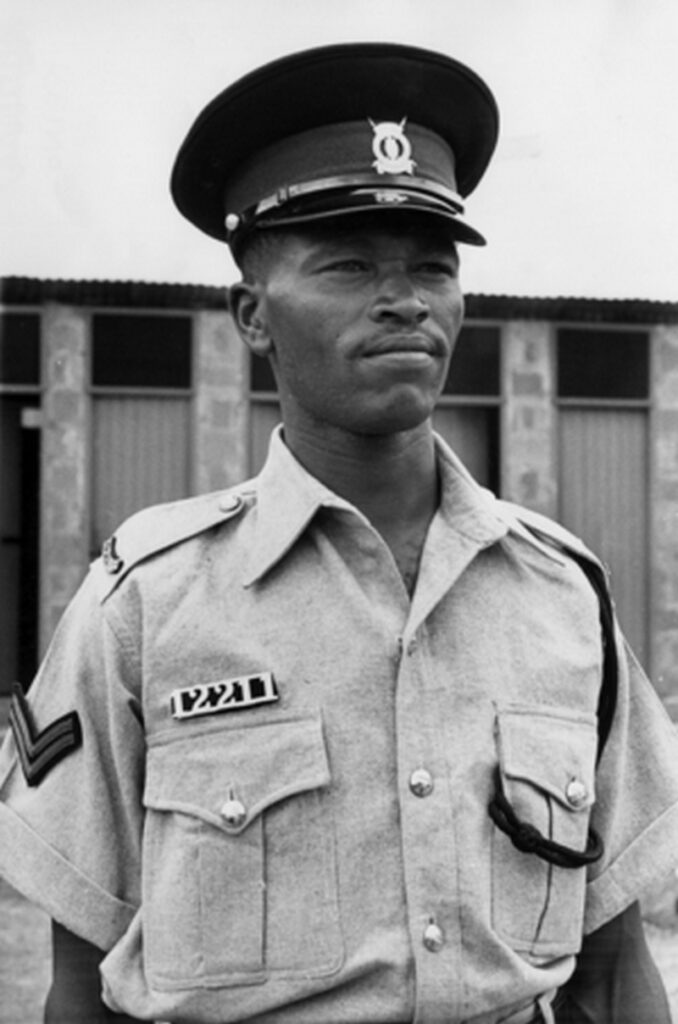

This November, I returned to Zanzibar. In my hotel room, I found a luxurious monograph, “Photographic Journey: 60 Years of the United Republic of Tanzania,” printed the previous year to commemorate 60 years since the unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar into modern-day Tanzania. In the chapter on the revolution, there is not a single mention of the roughly 20,000 Arabs and Indians killed on the island. Nothing about John Okello, the leader of the uprising, who claimed to have personally killed 8,000 people. Only the detail that it was the “fastest revolution” ever recorded—the coup began at midnight. By six in the morning, the new regime was already broadcasting official statements on the radio. What followed over the next two weeks chills the blood.

This revolution was unique in another, almost grotesque way: it became the only genocide in history captured almost in full on camera. An Italian documentary crew happened to be there filming Africa Addio, a film about the decolonisation of the African continent. From a helicopter, they recorded scenes that later made it into the movie: endless columns of Arab civilians marching along palm-lined roads, resembling a giant white serpent. When the helicopter descends, armed Black guards become visible, escorting them. Later, groups of roughly a hundred people at a time are separated and led into shallow, pre-dug pits, where they are executed.

An even more harrowing sequence takes place on the beaches: civilians—men, women, children—running towards the sea, some swimming, others scrambling onto overloaded, stranded boats in a desperate attempt to escape certain death. By the next morning, the waves of the Indian Ocean had washed ashore the bodies of most of them.

All of this was captured in painstaking detail, and footage from Africa Addio can be found on YouTube today—the video titled Arab Massacre in Zanzibar, uploaded by a descendant of one of the survivors.

American diplomat Donald Petterson described the killing of Arabs by the African majority as an act of genocide, writing: “Genocide was not a term that was as much in vogue then, as it came to be later, but it is fair to say that in parts of Zanzibar, the killing of Arabs was genocide, pure and simple.”

In the part of town where the Anglican Cathedral now stands, a slave market stood 145 years ago. Fifty thousand enslaved people were brought to Zanzibar each year, and after being sold at auction, their new owners transported them across Africa and Asia. Most were captured deep inside East Africa. David Livingstone calculated that more than 80,000 enslaved people died annually en route due to the brutal conditions of transport.

We entered the underground chambers where enslaved people were kept for three days before auction—without food, water, or light, in unbearable hygienic conditions, with only a tiny slit for air. In the left room, barely twenty square metres, around fifty enslaved men were held; in the right, of the same size, up to seventy women and children. I watched the horror on the faces of my daughters, aged twelve and fourteen, as they sat on the stone platforms listening to the guide.

Some enslaved people remained on Zanzibar to work on plantations. Nineteenth-century chronicles mention that the conditions were so harsh that Zanzibar was the only place where no slave revolt ever took place. Under heavy British pressure, the slave trade was abolished, but slavery itself was outlawed only in 1897, and some of its forms, such as forced marriage, persisted for decades.

Centuries of accumulated hatred exploded in the January Revolution of 1964. Victims and perpetrators in this case shared the same Islamic faith, as enslaved Black people had adopted Islam over centuries of Arab rule.

There is much to learn from this story—one unknown to most tourists who set foot on Zanzibar, and even fewer who have ever listened to Queen. It is a story about how people of the same religion but different origins can slaughter one another with the same cruelty seen elsewhere between people of the exact origin but different faiths. And about how long-buried frustration, left to ferment over generations, so often erupts into unimaginable violence in which the innocent pay the highest price.