A Journey into Armenia’s Heart, Between Faith and Fire

TRAVELOGUE

by Ivana Dukčević

During our journey through the South Caucasus, we reached Armenia, the southernmost of the three countries in the Caucasus region. At an elevation of 1,901 metres, we came upon the shores of Lake Sevan, the world’s second-largest high-altitude freshwater lake that is still navigable. Its name is believed to derive from the words “sev” and “vank” – “black” and “monastery” – after Sevanavank, the monastery founded on its shores in 874 by Armenian Princess Mariam. When it was built, the water level was higher, so the monastery stood on an island; today, it rises from an elongated peninsula on the lake’s western side.

Some 25 kilometres further south, we visited the village and cemetery of Noratus (or Noraduz) – Armenia’s most extensive and best-preserved medieval necropolis. Here, around eight hundred intricately carved tombstones stand, the oldest being khachkars (stone crosses) dating back to the ninth century.

Armenia became the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as a state religion

Long ago, Armenia was a land of restless volcanoes. Along the shores of Lake Sevan, we would find shards of obsidian – jet-black, glassy stones – and “moonstones” shimmering from pale white to soft green, once hurled from the craters of now-silent volcanoes. The memory of that fiery past lives on today in the quarrying of volcanic rock in countless hues, a building material that has been used for centuries in Armenia’s sacred and secular architecture.

The best example is the country’s capital, whose architecture is unlike any other. Built atop extinct volcanoes and in the shadow of the legendary Mount Ararat, Yerevan’s very fabric is volcanic tuff – a soft, workable stone. I have seen tuff elsewhere, but in Armenia it takes on a special character: blocks cut in a spectrum of colours, from ochre yellow and deep orange to brick red, smoky black, soft grey – and, most famously, a muted dusty rose that has earned Yerevan the name “the pink city.” While most buildings are clad in a single tone, many combine several, creating the effect of a mosaic across their facades. This volcanic stone is not only beautiful but practical: it breathes, keeps buildings temperate, and never needs painting.

Armenia’s capital lies cradled in a basin, at an average altitude of 990 metres. Parts of the city spill down steep slopes, with a difference in elevation of more than five hundred metres. Yerevan is the twelfth and last of Armenia’s historic capitals and is home to just over a million people – nearly a third of the country’s entire population.

At its heart lies Republic Square, framed by the government buildings and the imposing National History Museum. In front of the museum is a grand musical fountain that, on summer evenings, draws crowds as its dancing water jets shift colours and sway in time with classical symphonies and rock anthems alike.

A short stroll away is a leafy park that ends at Vernissage, the city’s open-air flea market, where silver jewellery, leather goods, woven fabrics, woodwork, and unique handcrafted souvenirs tempt every passer-by.

Yerevan’s very fabric is volcanic tuff – a soft, workable stone that breathes, keeps buildings temperate, and never needs painting

Further uphill, overlooking the city, stands the Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator. Gregory lived in the third and fourth centuries, embraced Christianity, and brought the new faith to the Armenian people. Thanks to him, in the year 301, Armenia became the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as a state religion, founding the Armenian Apostolic Church and installing Gregory as its first bishop.

Yerevan delighted me with its abundance of charming cafés, excellent yet inexpensive restaurants serving superb local cuisine, and street kiosks offering freshly pressed juices, chilled coffee crowned with whipped cream and ice cream, and frappés in endless flavours – especially around Charles Aznavour Square. This lively square is also known for its theatre, a whimsical fountain adorned with zodiac signs, and a giant chessboard with life-sized pieces. On warm summer evenings, young and old alike gather to play this game, which originated in neighbouring Persia (or possibly India). Fittingly, Armenia is the first – and so far only – country in the world to have made chess a compulsory subject for all schoolchildren in the second, third, and fourth grades since 2011.

Not far from the city centre, we wandered into Tamanyan Park, dotted with striking modern sculptures, which leads to the foot of the Cascade – Yerevan’s grand terraced staircase. At its summit lies the capital’s most famous viewpoint. From autumn to spring, on clear days free of haze, the panorama stretches across much of central Yerevan to the majestic stratovolcano Mount Ararat, rising some 35 kilometres away across the border in Turkey.

West of Republic Square, along the same street that hosts Armenia’s only Persian Shiite mosque, dating back to the eighteenth century, we stumbled upon a shop with beautifully arranged displays of dried fruit. Beyond the familiar apricots, peaches, plums, quinces, and figs, we discovered wonderfully chewy dried pears, cloud-soft dried apples, sour cherries stuffed with hazelnuts, and – most surprising of all – irresistibly sweet dried melon.

No visit to Yerevan would be complete without a stop at the legendary Ararat Brandy Factory, home to what is arguably the world’s most famous brandy. Although Ararat Brandy has been produced since 1887, the present building, which houses both the production facilities and the museum, was constructed in 1953, perched on a hill overlooking the heart of the capital. Ararat brandy is crafted from local white grapes grown in the vineyards of southern Armenia.

During the guided tour, we learned about the factory’s history and production process, watched how the brandy is made and stored, and admired the casks dedicated to visiting world-famous artists and politicians. Among the photographs on the walls, we spotted George Clooney, Peter Gabriel, John Malkovich, former Serbian president Tomislav Nikolić, Emir Kusturica, and, of course, Charles Aznavour – after whom one of the brandies is named. The tour concluded in a grand tasting hall, where we sampled Ararat brandy, featuring notes of apricot and coffee, paired with a walnut-topped piece of alva – a perfect harmony of aromas and flavours. Cheers! Or, as they say in Armenian, Kenac.

On warm summer evenings, young and old alike gather to play chess on a giant board in Charles Aznavour Square

On a high hill at Tsitsernakaberd, on the city’s quiet edge, we visited the Armenian Genocide Memorial and Museum. Built in 1967, the museum is strikingly modern and minimalist, featuring chronologically arranged black-and-white photographs, original documents, short films, and personal belongings, all dedicated to preserving the memory of the victims of the Armenian genocide in Ottoman Empire, which began in 1915.

Today, approximately three million people reside in Armenia, while nearly seven million Armenians comprise the diaspora worldwide. Outside of Russia and the United States, France remains home to the largest Armenian community – Charles Aznavour, born in Paris to Armenian refugee parents, being one of its most celebrated members.

In front of the museum, a park stretches where dozens of young fir trees have been planted by visiting heads of state. Beside one of them, a metal plaque reads: “From the President of the Republic of Serbia, Boris Tadić, 28.07.2009.”

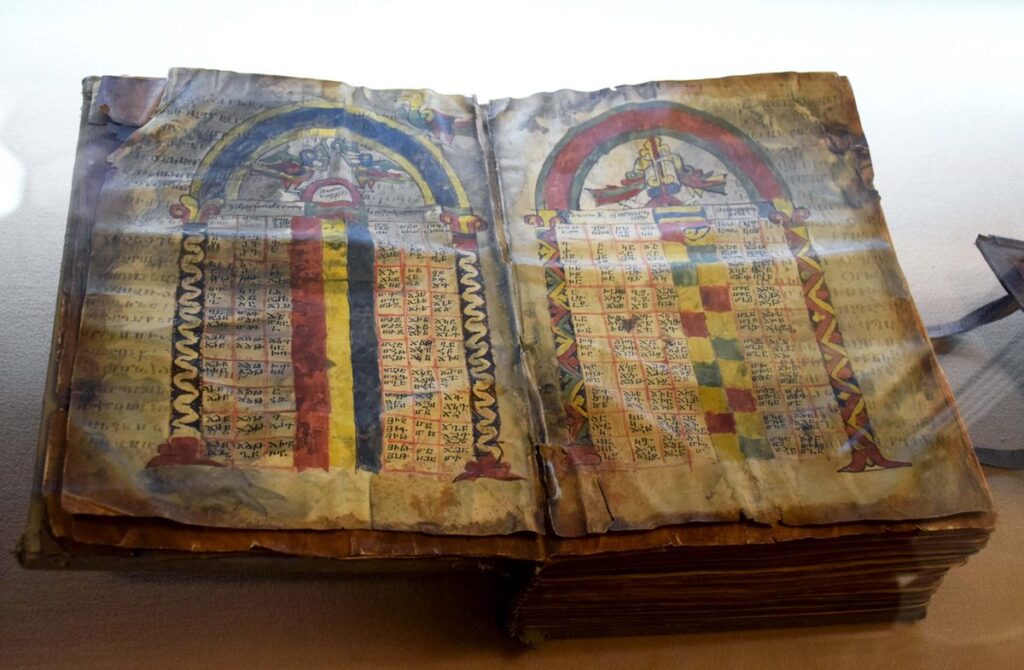

After visiting the Genocide Museum, we proceeded to one of Yerevan’s most important cultural institutions, the Matenadaran. Its name can be loosely translated as “the place where books are kept,” and it houses a priceless collection of medieval manuscripts and books, originally part of the Patriarchate’s library in Etchmiadzin and later taken under state protection. At the entrance, beneath the broad staircase, stands a statue of Mesrop Mashtots the monk who, in 405 AD, created the Armenian alphabet with its original thirty-six letters (three more were added later). The Armenian script is strikingly decorative, evoking the beauty of Eastern calligraphy. Some characters appear visually similar to those of Cyrillic or Latin alphabets, but their pronunciation is entirely different. Interestingly, until the introduction of Arabic numerals, Armenian letters also served as a means of representing numbers. Like neighbouring Persian, the Armenian language belongs to the Eastern branch of the Indo-European family, though it developed independently.

In a seemingly barren gorge, archaeologists uncovered some of the oldest wine storage vessels ever found – over six thousand years old

Eight kilometres south of the city centre, we continued to the Erebuni Museum and the Mesopotamian fortress of the same name, dating back to the eighth century BCE. Built by the people of Urartu (a name derived from “Ararat”), the ancestors of today’s Armenians, the fortress stood watch over what was then the northern edge of ancient Mesopotamia. Cuneiform inscriptions suggest that King Argishti I ordered the construction of the fortress and its citadel atop the hill of Arin Berd. The idea to turn the site into an open-air museum is inspired, but extensive excavations are still underway. So far, archaeologists have uncovered everyday household objects, bronze and agate jewellery, glassware, and statues of deities – all of which are now displayed in the museum at the foot of the hill.

West of Yerevan, in the shadow of the legendary Mount Ararat, we climbed a vineyard-covered hill to reach Khor Virap Monastery – one of Armenia’s most revered historic sites. It is here that King Tiridates III, in the late third century, imprisoned Gregory the Illuminator in a deep dungeon. After thirteen long years, struck by Gregory’s unwavering faith and endurance, the king freed him in 301 and embraced Christianity as the faith of his people. Tiridates thus became the first officially baptised ruler in history, and Armenia the first Christian nation in the world.

A short distance away, we visited Etchmiadzin (today Vagharshapat), the seat of the Armenian Church, where we saw Gregory’s church vestments and other treasured relics. This vast religious complex includes a museum, monastic quarters, and the Mother Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin – the spiritual heart of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Together with several nearby medieval churches, the complex is recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Not far from Etchmiadzin lie the ruins of the unique circular Zvartnots Cathedral, built in the seventh century. Its name translates as “Cathedral of the Heavenly Angels.” It was commissioned by the Catholicos of the Armenian Church at the time, when the patriarchal seat was relocated to this location.

Some of the most breathtaking landscapes in Armenia lie in the south, near the border with Iran, in the region of the picturesque Noravank Monastery and Armenia’s celebrated wine country. This corner of the country is defined by ochre-hued canyons and lush, green valleys threaded with streams. Along the way, we paused by orchards of pale-gold, succulent apricots – Armenia’s national fruit, cultivated here since antiquity. It was here, too, that we picked up a handful of what the Latins called prunus armeniacus – the “Armenian plum.”

In a seemingly barren gorge, we arrived at the village of Areni, home to Armenia’s most renowned wineries, which produce wine with a protected geographical origin. At one of them, the owner personally guided us through the production process before we sat down to taste the wine, paired with fish from the nearby stream.

Garni TempleA few kilometres further south, we turned off onto a side road and, before entering the canyon, climbed a long flight of steps to the Areni cave system. It was here, in 2007, that archaeologists uncovered some of the oldest wine storage vessels ever found – large, rounded clay jars built into the cave walls. These discoveries are believed to date back more than 6,000 years, to the Bronze Age.

From the main road, we turned into the canyon and soon reached the clifftop plateau where the thirteenth-century Noravank Monastery rises. Perched dramatically above the gorge of the Amaghu River, the complex is also known as “Noravank on the Amaghu.” Its most famous building is the two-storey Church of the Holy Mother of God, whose façade features an unusual external staircase built into the front wall – a striking piece of medieval Armenian architecture. The church is also called Burtelashen, meaning “built by Burtel,” in honour of Prince Burtel Orbelian, its benefactor.

Our journey concluded in the Yerevan basin, where we visited the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Geghard Monastery. Founded by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, Geghard is one of Armenia’s oldest and most important monasteries – and also one of its most visited. Its name, Geghardavank, means “the Monastery of the Spear,” referring to the relic it housed for centuries: the spear said to have pierced Christ’s side.

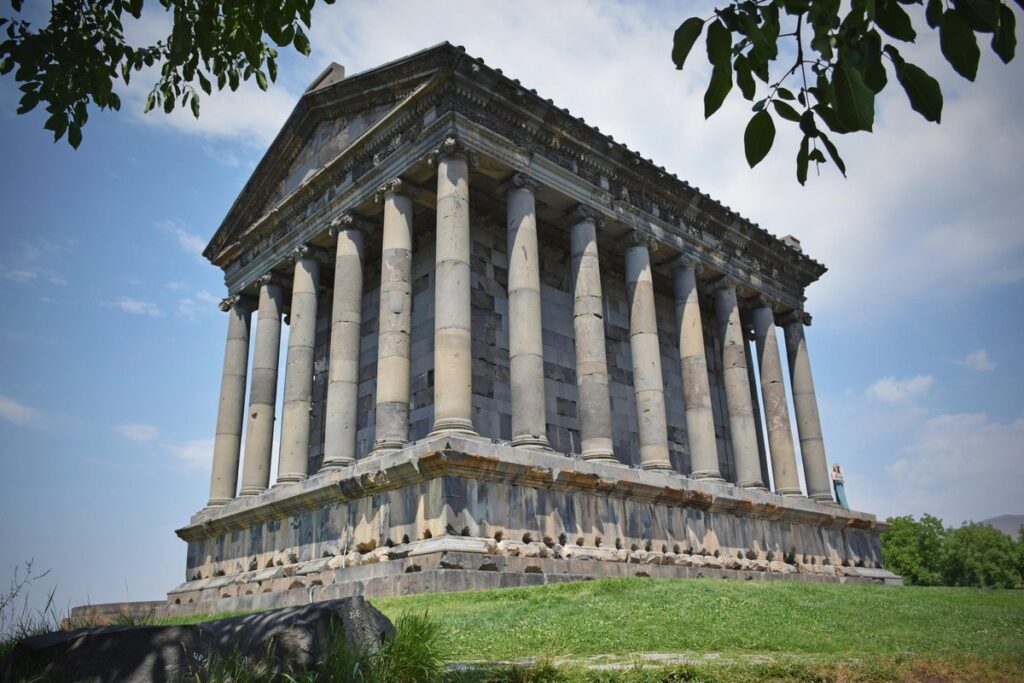

Nearby lies the Garni Temple, which, although it resembles something transported straight from the Mediterranean world, was in fact built by the ancient Armenians in the 1st century AD. Considered the oldest surviving pagan temple of the Armenian kings, it was commissioned in AD 76 by King Tiridates I and dedicated to the sun god.

The temple stands on a grassy promontory above the Garni Gorge. Below, along a winding road that follows the Azat River, the cliffs are lined with otherworldly stone formations – long, hexagonal basalt columns that appear to have been carefully placed by human hands. This natural wonder is poetically referred to as the “Symphony of Stones.”

All Photos: Ivana Dukčević