A journey through Israel’s uneasy present and echoes of its turbulent past

There are hardly any tourists or pilgrims in Jerusalem these days. Sirens warning of ballistic missiles launched by the Houthis from Yemen go off every three to four days. At the same time, young people play volleyball late into the night on Tel Aviv’s beaches – as if, just 70 kilometres further south on that same sand, a bloody war isn’t being fought.

There are hardly any tourists or pilgrims in Jerusalem these days. Sirens warning of ballistic missiles launched by the Houthis from Yemen go off every three to four days. At the same time, young people play volleyball late into the night on Tel Aviv’s beaches – as if, just 70 kilometres further south on that same sand, a bloody war isn’t being fought.

The sound of the siren woke me at 3 am on the seventh floor of the Dan Tel Aviv Hotel, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. I checked the website of a local daily. I saw that alarms had been triggered in numerous central Israeli cities, following the launch of a ballistic missile from Houthi positions in Yemen. Like most of those coming from that direction, the missile had been intercepted by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF).

I didn’t go to the shelter – the danger had already passed – but a colleague of mine had run to the “safe room” as soon as the siren sounded. Each hotel floor has one – a kind of concrete bunker. She said she found two Americans there in their underwear, who had jumped straight out of bed and beaten her to it.

“Blow the trumpet in Zion! Sound the alarm on my holy hill! Let all who live in the land tremble, for the day of the Lord is coming. It is close at hand,” I recalled the verse from the Bible. Air raid sirens have replaced the trumpets of Zion, and Israel has been living with this reality for nearly 77 years, ever since its founding.

“I believe that during your stay in Israel, you’ll have the chance to hear the sirens and head to a shelter – it happens every three or four days,” said Itay Milner, Head of the Media Department at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during a briefing in Jerusalem on our first day. A group of journalists from Serbia and Montenegro spent four days in Israel to better understand the country’s efforts to counter negative media narratives in many parts of the world, which have intensified since the start of the Gaza conflict in October 2023.

Milner told us that, with the help of AI, they’re collecting global media clippings: “For now, only in English – no need to worry!” he said with a smile. The project aims to help Israelis understand the roots of the issues facing both the country and Jewish communities worldwide over the past year and a half.

The morning after the air raid alert, we woke up to the news that two young employees of the Israeli Embassy in Washington had been killed. The suspect, Elias Rodriguez, was arrested at the scene and confessed to the murders, saying he had done it “for Gaza.” The attack happened as the two staff members were leaving an event at a museum. According to officials, the assailant shot them at close range. Both victims – a man and a woman – died on the spot. The killer, of Latino background and not a Muslim, repeatedly shouted “Free Palestine!”

This news was a stark confirmation of what we had discussed with Itay Milner on our first day at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both Israel and Jews across the globe – even in traditionally allied countries like the United States – are facing a serious issue. It’s not just about reputation, nor is it confined to Muslim communities.

This news was a stark confirmation of what we had discussed with Itay Milner on our first day at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both Israel and Jews across the globe – even in traditionally allied countries like the United States – are facing a serious issue. It’s not just about reputation, nor is it confined to Muslim communities.

Milner expressed particular frustration with some European countries, whose officials, he claims, sometimes make harsher statements about Israel than others in the region. For instance, the foreign minister of the UAE recently stated that the release of all hostages must be a precondition for the resumption of peace talks. The UAE, along with Bahrain, was part of the Abraham Accords – an agreement brokered by Donald Trump in September 2020, near the end of his first term, which normalised relations between Israel and the two Gulf Arab states.

Itay Milner believes that the October 7th attack was, in part, intended to halt the expansion of the Abraham Accords – the normalisation of relations with Israel – to additional Arab countries, particularly the region’s key player, Saudi Arabia.

Those of us who follow the diplomatic scene in Belgrade are well aware that ambassadors from certain Arab and Islamic countries are strictly forbidden from shaking hands, toasting, or even appearing in the same photograph as the Israeli ambassador. Among the countries with embassies in Belgrade that enforce such restrictions are Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Syria, Lebanon, and Iran. Time will tell whether Trump, if re-elected, will manage to extend the Abraham Accords to more Arab and Islamic nations.

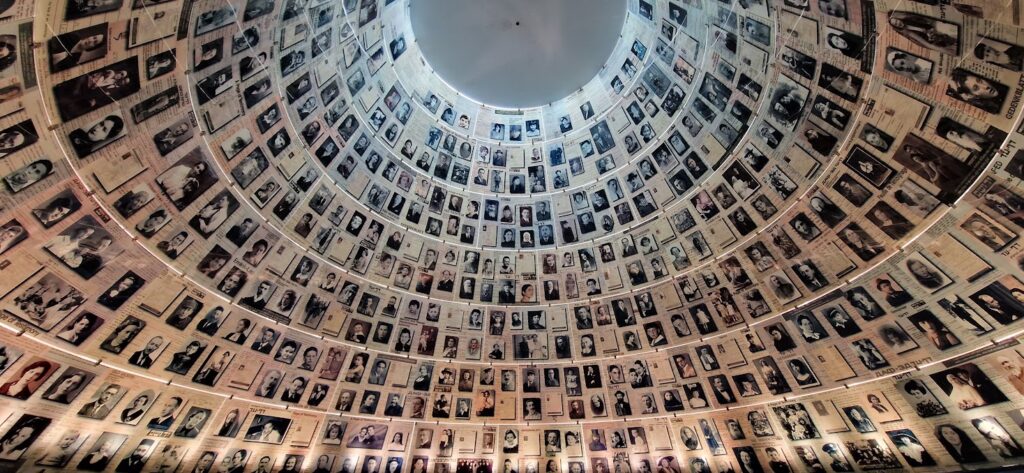

On our first day, we visited Yad Vashem – the museum and memorial complex dedicated to Holocaust victims, as well as to the “Righteous Among the Nations,” those across Europe who risked their lives to hide and save Jews during World War II. When I first visited Yad Vashem in 1998, on the occasion of Israel’s 50th anniversary, I was part of a delegation of Serbian city officials twinned with Israeli cities, led by Klara Mandić. Since then, in 2005, a new museum building was opened. Yad Vashem was established in 1953 and covers 18 hectares on the western slopes of Mount Herzl.

Our guide through the museum was an elderly woman whose parents were among the few Polish Jews to survive the Holocaust. The museum was packed – not with tourists, but with members of the IDF: young men and women in uniform learning about what happened to their ancestors in Europe more than 80 years ago.

Our guide through the museum was an elderly woman whose parents were among the few Polish Jews to survive the Holocaust. The museum was packed – not with tourists, but with members of the IDF: young men and women in uniform learning about what happened to their ancestors in Europe more than 80 years ago.

We then headed to Jerusalem’s Old City, which, unlike my previous visits in 1998 and 2014, when it was nearly impossible to walk through the crowds, now felt pleasantly quiet. Souvenir shop owners and other workers in the Old City lament that they had only just begun to recover in 2022 after two pandemic years with virtually no tourists, only to be struck again in 2023 by the Hamas attack on October 7th and the ensuing war in Gaza. That conflict continues to deter many pilgrims and tourists from visiting the city’s holy sites. Aside from a few locals, the streets were mostly empty, except for a handful of small groups attending international conferences held in Israel’s capital.

Inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, I shared a story with my fellow travellers from a visit back in 1998, when among the Serbian delegation was Živorad Igić (1942–2003), then President of the Provincial Committee of the Socialist Party of Serbia for Kosovo and Metohija. Unlike some other politicians on the trip, Živorad was kind and likeable. He moved quietly through the church, attentively listening to the guide and jotting everything down in a small notebook. I asked him what he was doing.

“Crucified? Rose on the third day? This is fascinating material. I’m going to publish it all with my friend Radević in the Novi Sad daily Dnevnik,” he replied. I didn’t have the heart to tell him the story had already been written – and that it’s called the Bible.

After my second visit to Israel in 2014, I wrote a piece for the Facebook page of the Israeli Embassy in Belgrade titled Where Does Our Antisemitism Come From? During a day trip to Jerusalem from a cruise ship docked in the port of Haifa, I was taken aback by the open antisemitism expressed by many in our group throughout the bus ride. Whispered comments flew around: “They only care about money and gold!”, or bizarre questions like, “How do you explain that no Jews died in the 9/11 Twin Tower attacks?” (!?). After the guide retold Moses leading the Israelites out of Egyptian slavery, someone said, “Aha, so it was our guy – a Christian – who saved them!”

It’s important to note that these weren’t uneducated villagers from rural eastern Serbia or hot-headed teenagers. These were people from the so-called “upper middle class,” the kind who can afford a ten-day cruise: business owners, car dealership operators, former directors of socialist-era industrial giants – men and women between 40 and 60 years old. I’m pretty sure none of them had ever even met a Jew in their lives. No Jewish boss ever made their life difficult, no Jew ever “poisoned their water.”

It’s important to note that these weren’t uneducated villagers from rural eastern Serbia or hot-headed teenagers. These were people from the so-called “upper middle class,” the kind who can afford a ten-day cruise: business owners, car dealership operators, former directors of socialist-era industrial giants – men and women between 40 and 60 years old. I’m pretty sure none of them had ever even met a Jew in their lives. No Jewish boss ever made their life difficult, no Jew ever “poisoned their water.”

So, how does someone in Serbia grow to harbour such antisemitism? I believe the root lies in the propaganda during Milošević’s era, particularly during the NATO bombing, when figures like Madeleine Albright, George Soros, and “the American Jews” were blamed for everything. That’s what singers Maja Nikolić and Miloš Bojanić were referring to when, in 2014, they publicly stated on reality TV – watched by millions – that they hated Jews “because they bombed Serbia.”

Each hotel floor has a safe room – a kind of concrete bunker

The second reason is universal – we tend to dislike those who are more successful and wealthier than we are. Those who make up just 0.1% of the world’s population account for 40% of Nobel Prize winners in medicine. Those who, in the 1967 war, fought against all four of their neighbours and, in just six days, captured the Golan Heights, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza, and Sinai. We, with a similar population size, have barely produced one Nobel laureate and, after a century of warfare, ended up losing everything there was to lose.

The third reason is ignorance. When someone says Moses was “a Christian who saved the Jews from Egyptian slavery” – while also claiming to be a believer, regularly attending church, and celebrating religious holidays – you can’t expect much understanding of global historical currents.

The third reason is ignorance. When someone says Moses was “a Christian who saved the Jews from Egyptian slavery” – while also claiming to be a believer, regularly attending church, and celebrating religious holidays – you can’t expect much understanding of global historical currents.

This time, our group consisted of 15 journalists from Serbia and Montenegro, and thankfully, there were no such comments. There were fair, rational questions posed to our Israeli hosts regarding the disproportionate and indiscriminate use of force in Gaza, but no antisemitism or basic historical confusion.

However, every post I shared on social media during this trip, especially the video from the memorial site of the Nova Festival massacre, was flooded with openly antisemitic comments.

From one of the shops in the Old City, I heard the song Jerusalem of Gold (Yerushalayim Shel Zahav) – the same melody Steven Spielberg used in the final scene of Schindler’s List, when the surviving Jews walk free from the camp. The film shifts into colour as the real-life “Schindler Jews,” with their children and grandchildren, place pebbles on Oskar and Emilie Schindler’s grave.

The song was written in 1967 by Naomi Shemer. After the Six-Day War that same year, when Israeli soldiers reached the walls of the former Temple of Solomon and began singing Jerusalem of Gold, it became something of an unofficial national anthem of the Jewish state.

“The Wailing Wall is a misnomer for what is the Western Wall of Solomon’s Temple,” our guide explains, noting that mourning takes place there only once a year, on the day of the Temple’s destruction. On the remaining 364 days, the atmosphere is one of celebration and life. Even those of us who are not Jewish are welcome to approach the wall, touch it, slip in a note with a wish or prayer, or sit on one of the plastic chairs in front of it and take in the ambience. Men pray on the left, women on the right, separated by a tall divider.

The next day, we headed south, near the town of Netivot, close to the Gaza border, to a memorial known as the Car Wall. It’s a structure made up of 1,600 burned or destroyed vehicles, collected from Highway 232, where many of the victims of the October 7th Hamas attack were killed while fleeing the Nova music festival. Many of the cars still contain the belongings of those who were murdered inside, and next to each vehicle are photographs of the victims. One of the most harrowing stories involved an ambulance where 18 festivalgoers had taken shelter – among them, a wheelchair-bound young woman whose father had taken her to the festival. They were all either shot, bombed, or burned alive by Hamas terrorists.

The next day, we headed south, near the town of Netivot, close to the Gaza border, to a memorial known as the Car Wall. It’s a structure made up of 1,600 burned or destroyed vehicles, collected from Highway 232, where many of the victims of the October 7th Hamas attack were killed while fleeing the Nova music festival. Many of the cars still contain the belongings of those who were murdered inside, and next to each vehicle are photographs of the victims. One of the most harrowing stories involved an ambulance where 18 festivalgoers had taken shelter – among them, a wheelchair-bound young woman whose father had taken her to the festival. They were all either shot, bombed, or burned alive by Hamas terrorists.

We continued further south and arrived at the site of the Nova festival massacre. On October 7, 2023, Hamas terrorists stormed the festival grounds in the early morning and killed 378 people – 344 were attendees, while 34 were security staff and police officers. Hen Malka, a survivor of the massacre, shared her traumatic story with us. She said that each time she recounts what happened, she relives the horror and thinks of her friends who were murdered – but that she sees it as her duty to help ensure such things never happen again.

Among the photographs of the victims is that of Mor Cohen, the grandson of Dušan Mihalek from Novi Sad, and Alon Ohel, whose parents also have roots in Novi Sad. He was abducted during the festival, and his fate remains unknown.

We tend to dislike those who are more successful and wealthier than we are

Itai Anghel (57) is one of Israel’s most seasoned war correspondents. Over the past 35 years, he has reported from nearly every major conflict zone across the globe — from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the wars in Croatia, Bosnia and Rwanda, to the latest eruptions of violence in the Middle East. A year before Željko Ražnatović, Arkan, was assassinated in Belgrade’s Intercontinental Hotel, Anghel interviewed him in that very place.

We met with Anghel in a Tel Aviv hotel, where he spoke to us about the wars he has witnessed and, with a palpable sense of urgency, the current situation unfolding in Gaza.

The following day, we travelled north to the Misgav Am viewpoint in the Golan Heights, where the Syrian border stretches out before you like a map. There, David Baruh, a reservist major in the Israeli army, walked us through the military history of the area — from the moment Israeli forces took control of the Golan in the Six-Day War of 1967, to the simmering tensions that persist to this day.

Not far from there lies Majdal Shams, a Druze village where, on 27 July last year — just as the eyes of the world turned to Paris for the opening of the Olympic Games — a horrific tragedy unfolded. A rocket, fired from Hezbollah-controlled territory in Lebanon, struck a children’s football pitch in the heart of the village. Twelve children were killed instantly — ten boys and two girls.

We spoke with the parents of the victims, who shared how they’ve found the strength to carry on. As they told their stories, a group of local children was back on the same pitch, kicking a ball under the same sky.

Later, we were welcomed into a Druze home nearby, where our host, a warm and spirited woman, prepared a delicious traditional meal and shared with us the customs and beliefs of her community. The Druze believe in reincarnation: when someone dies, their soul passes into a newborn. That’s why, after the funeral, the family no longer visits the grave — doing so, they believe, would disturb the baby now carrying the spirit of the deceased.

Later, we were welcomed into a Druze home nearby, where our host, a warm and spirited woman, prepared a delicious traditional meal and shared with us the customs and beliefs of her community. The Druze believe in reincarnation: when someone dies, their soul passes into a newborn. That’s why, after the funeral, the family no longer visits the grave — doing so, they believe, would disturb the baby now carrying the spirit of the deceased.

The Druze flag, a vibrant spectrum not unlike the Rastafarian one, hung near family portraits on the wall. Our host’s husband, who was once a history professor in Damascus during the era when the Golan was still under Syrian control, proudly showed us photos of his ancestors and family.

The atmosphere is one of celebration and life

The Druze faith emerged in the 11th century as an offshoot of Ismaili Islam, blending gnostic and neoplatonic philosophies into a unique spiritual doctrine. They speak Arabic and follow social customs similar to those of other Arabs in the region. While many Muslims do not consider the Druze part of Islam, the Druze themselves identify as Muslims. Today, their population stands at roughly 360,000 in Lebanon, 280,000 in Syria, 125,300 in Israel, 20,000 in Jordan, and smaller diaspora communities in the United States.

Yahel Vilan served as Israel’s ambassador in Belgrade until August last year, and it took me quite some time, over coffee in a hotel lobby, to explain what is currently happening in Serbia. He now represents the Israeli government in matters related to the Expo in Osaka this year, as well as the one scheduled for Belgrade in 2027, and he is looking forward to returning to our country.

Yahel Vilan served as Israel’s ambassador in Belgrade until August last year, and it took me quite some time, over coffee in a hotel lobby, to explain what is currently happening in Serbia. He now represents the Israeli government in matters related to the Expo in Osaka this year, as well as the one scheduled for Belgrade in 2027, and he is looking forward to returning to our country.

While the rest of the group headed to dinner, I decided to take a swim in the sea, followed by a stroll along the beautifully arranged promenade to reach my daily goal of 10,000 steps — faithfully tracked by the app on my phone. At 10 p.m., the beaches were packed with young Israelis playing beach volleyball, running, cycling…

My colleague Zlatko Crnogorac responded to my post on the social network X by sharing a poster for the film The Zone of Interest, comparing the carefree beach atmosphere to the film’s central theme: we’re enjoying ourselves by the sea, while on the other side of the fence — in this case, Gaza — lies Auschwitz.

Without delving into whether such comparisons are appropriate, the fact remains that, for the first time, the Jewish people, who for decades held an almost exclusive position as victims, are now facing a massive wave of condemnation over what has unfolded in Gaza over the past year and a half.

Without delving into whether such comparisons are appropriate, the fact remains that, for the first time, the Jewish people, who for decades held an almost exclusive position as victims, are now facing a massive wave of condemnation over what has unfolded in Gaza over the past year and a half.

She relives the horror every time she tells the story

On our final day, after the morning siren mentioned at the beginning of this piece, we arrive at Hostage Square in central Tel Aviv, where we are met by Idit Ohel, the mother of Alon Ohel — a young pianist abducted from the Nova music festival on 7 October. At the heart of the square stands Alon’s yellow piano, where passers-by are invited to play as they look upon his photograph and the message: #BringThemBack. That morning marked 394 days since Alon was taken into captivity.

Joining us is Yossi Levy, Israel’s ambassador to Serbia from 2011 to 2022. Levy was the first openly gay foreign ambassador posted to Belgrade, arriving with his husband, a Polish national. Despite Serbia’s often homophobic climate, Levy became one of the most well-liked and respected diplomats in the city, thanks mainly to his social acumen and warm presence. He has since written a novel set in the fictional country of Slavia, which happens to share borders with Bosnia, Bulgaria and Montenegro. The manuscript is currently with a Serbian publisher, and from what we hear, quite a few readers may recognise themselves between the lines.

Also arriving at Hostage Square is Dušan Mihalek, originally from Novi Sad. In 1991, he emigrated to Israel with his wife and four children, determined to prevent his eldest son from being drafted and sent to the siege of Vukovar. Three decades later, tragedy struck again — his grandson, Mor, was killed thousands of miles away during the Hamas attack at the Nova festival. Mor had stayed at home while his mother, Dušan’s daughter, visited her grandmother in Novi Sad. He went to the festival with a friend. The friend survived. Mor did not.

Soon after arriving in Israel back in 1991, Dušan learned Hebrew and became a tour guide. We had the privilege of hearing him speak on the bus from Hostage Square to the Start-Up Nation headquarters — offering commentary on the streets we passed, lesser-known anecdotes from Tel Aviv’s and Israel’s history, and the centuries-old ties between the Jewish and Serbian peoples.

Soon after arriving in Israel back in 1991, Dušan learned Hebrew and became a tour guide. We had the privilege of hearing him speak on the bus from Hostage Square to the Start-Up Nation headquarters — offering commentary on the streets we passed, lesser-known anecdotes from Tel Aviv’s and Israel’s history, and the centuries-old ties between the Jewish and Serbian peoples.

Over lunch, everyone was glued to their phones, anxiously tracking the news of yet another ballistic missile launched by the Houthis — one that had the potential to disrupt our flight back to Belgrade. By the time we reached Ben Gurion Airport, we saw that several flights, including the one to Paris, had been cancelled. Fortunately, the El Al flight to Belgrade taxied off on time, and only once we had safely left Israeli airspace and begun our descent towards Cyprus did a wave of relief wash over the cabin, not unlike the final scene in Argo, when the wheels leave the tarmac. The passengers know they are genuinely free.

When someone dies, their soul passes into a newborn

Dragica and Olga Bartulović – Righteous Among the Nations

As we left the Yad Vashem museum and walked through the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations — where a tree is planted for every person who saved at least one Jew during the Holocaust — we passed plaques dedicated to Oskar and Emilie Schindler, as well as Dragica and Olga Bartulović from Croatia. While Schindler’s story is widely known, who were Olga and Dragica?

These two Serbian women from Split risked their lives to save the Nahmijas family, Jews from Banja Luka.

In April 1941, with the outbreak of war and the annexation of Banja Luka and the rest of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Nazi puppet state of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), Samuel Nahmijas — a respected merchant — left for Belgrade, seeking refuge with his mother. His wife Erna and their three children were to join him later. But once the Ustaše authorities discovered Samuel had fled, they arrested Erna and only released her after she paid an enormous ransom. Realising the danger, she had to flee immediately with the children. Belgrade was no longer an option — Jews there were already being rounded up and executed.

A family friend, a lawyer, advised her to head to Dalmatia, then under Italian occupation. He managed to secure forged documents identifying them as Croats from Split.

In Split, Erna connected with members of the local Jewish community and sent a document to her husband, “proving” that he, too, was from Split, in the hope that it would secure him a travel permit. Not long after, a newspaper clipping arrived listing hostages executed at Tašmajdan — and among them, the name Samuel Nahmijas. However, one day, Samuel appeared at their door. It turned out it was his cousin who had been shot.

In Split, Erna connected with members of the local Jewish community and sent a document to her husband, “proving” that he, too, was from Split, in the hope that it would secure him a travel permit. Not long after, a newspaper clipping arrived listing hostages executed at Tašmajdan — and among them, the name Samuel Nahmijas. However, one day, Samuel appeared at their door. It turned out it was his cousin who had been shot.

Two years later, following Italy’s capitulation in 1943, German forces entered Split and immediately issued posters demanding that all Jews register with the authorities. Erna, Samuel and the children were again in danger. In the same building on Omiška Street where the Nahmijas family was staying, Olga Bartulović, secretly connected to the Partisan movement, lived. She hid Erna and the children in an Orthodox monastery, while she and her sister-in-law, Dragica, led Samuel into the woods.

At the monastery, the family posed as refugees from Serbia. A month later, Olga returned to collect the eldest son, Lazo, and eventually came back for the younger two children as well. Once all three children and Samuel were safely behind Partisan lines, Dragica came for Erna. Dressed as peasant women, they headed to market, passing through numerous military and police checkpoints, and finally reunited with the family.

Thanks to the extraordinary courage and humanity of Dragica and Olga Bartulović, the Nahmijas family survived the Holocaust.