From Medieval Builders to Novi Sad’s Lost Church – Tracing Centuries of a Community’s Presence

ARMENIAN HERITAGE IN SERBIA

by Vladimir Petrović

Armenians were described in the 16th century in the Balkans as skilled merchants, stonemasons, and builders. This community left a deep imprint on Serbian territories, which, apart from a single monument in Novi Sad, is today almost entirely unmarked.

There are no precise records about the earliest settlement of Armenians in the Balkans. Most likely, their migration from the Caucasus to these lands occurred during the 10th and 11th centuries, following the advance of the Turks and the fall of the then Armenian capital, Ani, to Turkish control in 1064.

According to tradition, Armenians came to Serbia at the invitation of Saint Sava, who was reportedly impressed by their architectural achievements. They accepted this invitation and, again according to tradition, first built the Vitovnica Monastery in the Braničevo district. However, this monastery was actually founded much later, at the end of the 13th century, during the reign of King Milutin, although Armenian builders did indeed participate in its construction. This is evidenced by a bilingual donor’s plaque at the monastery, which reads: “In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, I, Ladon, Babug’s son, built this church in the name of Saint Jacob the Patriarch and Saint Peter the Apostle for the remembrance of myself and my parents (…) in the year 667 of the Armenian calendar.”

Monument in Novi Sad hides the tomb of the Čenazi family and other Armenians

Later traditions about the Battle of Kosovo also mention an Armenian detachment that was part of the Ottoman army but switched to the Serbian side during the battle. The surviving members of this detachment were said to have settled in the area around Sokobanja afterwards, where they founded a monastery named Jermenčić. However, as there are no material traces of this, the story most likely belongs to the realm of legend.

Armenians in Novi Sad

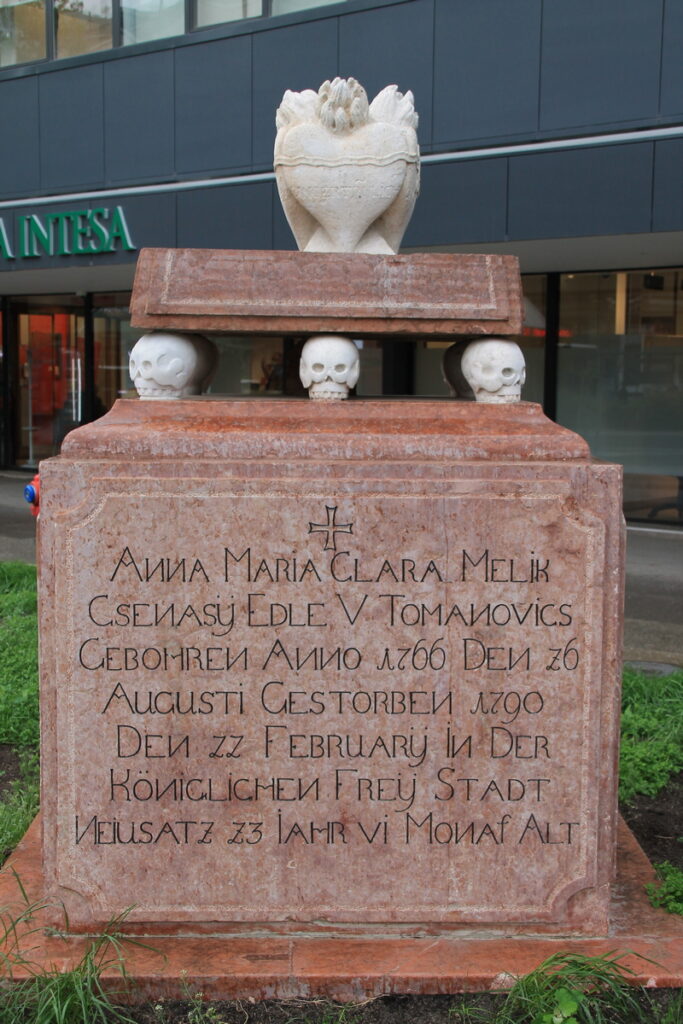

On the pavement of one of Novi Sad’s busiest streets, in Mihajlo Pupin Boulevard, near the underpass and bus stop, a monument has stood for decades. It is unclear what intrigues more – the names carved into the pink stone pedestal, the text inscribed in an archaic form of German, or the white marble skulls at the top of the pedestal, holding another plaque that bears flaming hearts and the word: “Inseparable.”

For most passers-by, what this monument represents remains a mystery – as does the fact that beneath it lies a tomb containing the remains of the Armenian Čenazi family and numerous other Armenians. In the immediate vicinity of the monument, on the site of today’s business complex, stood an Armenian church as recently as six decades ago.

Armenian builders took part in the construction of Vitovnica Monastery in the 13th century

Written records of the presence of Armenians in the Balkans are sporadic until the 16th century, when they appear in the historical record as skilled merchants and craftsmen. The first prominent recorded members of Belgrade’s Armenian community were Aslan and Alpiar Bagratuni, who settled in Belgrade in 1521, as documented in a record kept at the Armenian Monastery in Venice. It states that the two of them generously supported the Armenian church in Belgrade.

This Armenian church was located near Obilićev venac, where three 17th-century tombstones were discovered during archaeological excavations. Their exceptional artistic value confirmed the perception of Armenians as master stonemasons and builders. These three slabs are now displayed outdoors at Kalemegdan, near the Republic Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments.

Armenians in Vojvodina

In 1739, when Ottoman forces captured Belgrade, the city’s Armenian community crossed the Danube together with the Serbs. Upon their arrival in Vojvodina, Armenians were granted nearly full religious rights, primarily within the framework of the Armenian Catholic Church, which soon became the sole Armenian religious community in the region.

Marija Trandafil financed the rebuilding of the Armenian church in 1872

The Armenian colony, numbering around 150 members, was settled near the Petrovaradin Fortress. In Novi Sad, Armenians became renowned for their expertise in trading wool, spices, coffee, sugar, and precious metals, later expanding their presence to other parts of Vojvodina, particularly Banat, where some wealthy Armenians acquired large estates.

One of the wealthiest and most prominent landowning families in Vojvodina was the Armenian Čenazi family, who had moved to Novi Sad from Belgrade in 1739. Thanks to them, the Armenian church was built in the city, and for several generations, members of this family served as city senators. The family’s wealth and influence are also evidenced by the preserved family tomb in Novi Sad, where Simeon Čenazi, married to Ana Marija Klara Tomanović, is buried. Over time, the family declined and its descendants dispersed. In addition to the Čenazi, other notable Armenian families included Avedik, Agamal, Minar, Markar, and others.

The First Armenian Church

Shortly after their move from Belgrade to Novi Sad in 1739, construction began on the first Armenian church. It was located a few hundred metres from today’s Liberty Square. The building of the church, dedicated to Saint Gregory the Illuminator, and the parish house began in 1744 and was completed two years later. The church’s largest benefactor was Jovan Čenazi, who also served as a city senator for a time. His tomb bore the inscription: “Mr Joanes Džan azizjan Šorotski, lived here for a time in exile. He was a good man and helped the poor, lived for sixty-seven years and then departed to the Lord in a gentle death and was buried in this splendid grave.”

No photographs of the old church have been preserved, nor detailed descriptions of its appearance. In old drawings, the Armenian church was not clearly visible, although it was marked on the 1774 engraving by Zaharia Orfelin.

The New Armenian Church in Novi Sad

A turning point in the history of Novi Sad – one that also deeply affected the Armenian community – occurred in 1849 during the revolution, when Hungarian forces from the Petrovaradin Fortress shelled the city centre in response to General Josip Jelačić’s attempt to seize the fortress. Dozens of cannonballs set off fires that destroyed a large number of houses and almost all public and religious buildings, including the Armenian church. The church was reduced to rubble, and its inventory looted. Although contributions for rebuilding the church were collected from Armenian communities throughout Austria-Hungary, reconstruction did not take place for nearly two decades. The turning point came thanks to one of Novi Sad’s wealthiest women, Marija Trandafil, who, after her husband’s death, dedicated herself to philanthropy. In addition to scholarships for poor children, she used her own funds to finance the restoration of Orthodox churches in the city, as well as the Armenian one.

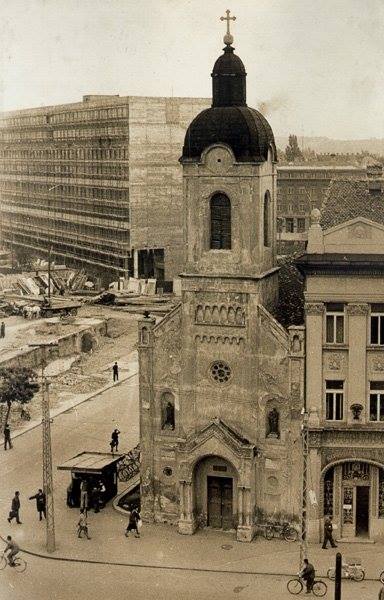

Construction of the new church began in 1872. Although the original plan by renowned architect Đerđ Molnar (who also designed the City Hall and the Church of the Name of Mary in Novi Sad) envisaged a building in the then-dominant Baroque style, this idea was abandoned. Numerous Neo-Gothic elements were introduced into the project, and the height of the tower was increased to nearly 29 metres. Upon completion, a commemorative plaque was placed on the church façade with an inscription in Serbian: “To the glory of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, and out of humble and pure Christian love for her fellow men, Marija Trandafil rebuilt this House of God, 1872.”

Although the new church was completed, several years passed before it was consecrated and regular services began. The disappearance of Novi Sad’s Armenian community led to a rather negligent attitude by state and city authorities toward the maintenance of the Armenian church.

The church was demolished in 1963 despite protests from heritage institutions

By the 1950s, the already dilapidated church was being maintained by Johan Samuel Polikarp, but this task had become nearly impossible. Since he was the last Armenian left in the city – the last Armenian woman of Novi Sad had died in 1948 – the Mekhitarists decided to sell the church to a Catholic order, initially the Franciscans, with the idea of using the funds to build a church in Belgrade, where a small Armenian community had formed after the First World War – but this plan was never realised.

Demolition of the Church

As the urban development plans foresaw the demolition of the Armenian church in Novi Sad, and since Roman Catholic orders were unwilling to purchase it, the building was left to decay. During a major storm in 1957, the church’s roof was almost destroyed and never repaired.

Then, due to the construction of a new boulevard through the city centre – today’s Mihajlo Pupin Boulevard – and despite protests from urban planners and the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments, a final decision to demolish the church was made in 1963.

The only remaining trace of the Armenian community is the aforementioned Čenazi family tombstone, now protected as a cultural monument of great importance. Originally located in the courtyard of the Armenian church, it was moved several times before finding its current place on Mihajlo Pupin Boulevard in the early 1990s.

Around the same time, an Armenian cross – a khachkar – was erected nearby as a memorial to the Yugoslav pilots who died in 1988 while transporting humanitarian aid to the victims of the Armenian earthquake.

Other surviving traces of the Armenians’ centuries-long presence in Serbia include three previously mentioned tombstones displayed at Kalemegdan, as well as a khachkar in the park in Zemun, installed in the 1990s and frequently desecrated by vandals. The centuries-old history of Armenians in this region has largely been forgotten.

Armenians in Belgrade

Armenians left a significant mark on the scientific and cultural life of Belgrade. Among them were doctors Vramšapuh Ataljanc and Amajak Muradijan, an engineer, university professor and member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Jakov Hlitčijev, astrophysicist and director of the Belgrade Observatory Vasilije Vahe Oskanjan, ballet star Ašhen Ataljanc, graphic designers and illustrators from the Vartabedijan family of Armenian descent, as well as composer Vartkes Baronijan, who, among other works, composed music for Dositej Obradović’s poem Arise, Serbia for the 1990 TV series The Pillow of My Grave, written by Slobodan Stojanović and produced by Television Belgrade.

The full text on Armenians and their heritage by Vladimir Petrović can be read at oko.rts.rs. This excerpt is published with the permission of the author and RTS.