A global perspective on injustice, resilience, and the urgent need for meaningful change

POSTCARD INTERVIEW

by Žikica Milošević

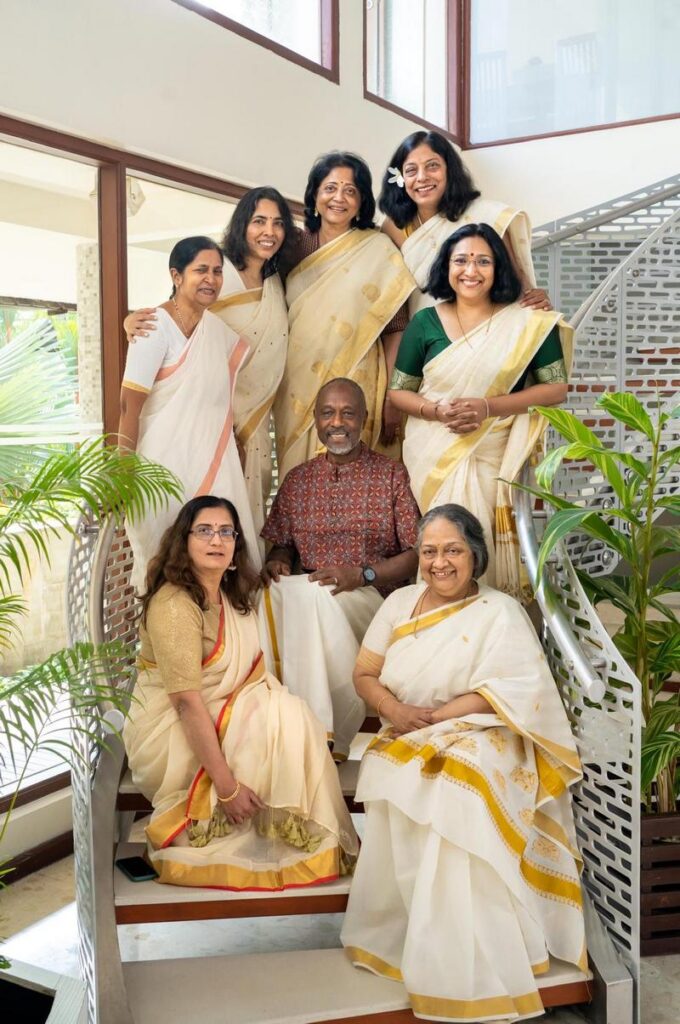

The charismatic former head of the UNICEF mission in Serbia, Michel Saint-Lot, a Haitian with permanent residence in France, is a frequent visitor to Serbia, which has left an excellent impression on him. We discuss with him the ongoing challenges in his homeland, in the world, and in the places where he served after Serbia, as well as memories from our country.

Working for UNICEF, you encountered many problems in faraway parts of the world, and for several years, the situation in your homeland, Haiti, has been terrible. What are the biggest challenges in Haiti at the moment?

Haiti today is in the grip of a worsening crisis—one shaped by political collapse, unchecked gang violence, and deepening humanitarian need. Since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021—carried out by Colombian ex-military personnel and allegedly involving members of the Haitian police—governance has unravelled. There’s been no elected leadership since. Instead, a nine-member transitional council, lacking both legitimacy and public trust, has struggled to steer the country forward.

Some continue to question whether foreign actors played a role in Moïse’s killing, given the background of the mercenaries and the long history of U.S. involvement in Haitian affairs. Today, around 90% of Port-au-Prince is reportedly under gang control. Necessities—food, fuel, medicine—are blocked from reaching large parts of the city. Over half the population is going hungry, and more than 60% live on less than $3.65 a day. Famine, displacement, and fear dominate daily life.

The Transitional Presidential Council (CPT), supported by the U.S., Canada, France, and CARICOM, was intended to provide stability. But for many Haitians, it represents more of the same: a disconnected, unelected body bogged down by infighting and seen as corrupt or ineffective.

Meanwhile, armed groups like Viv Ansam function as de facto rulers in much of the capital. They’ve blocked supply routes, triggered mass displacement (over 1.3 million people), and outgunned the national police. The long-awaited UN-backed international security mission has barely gotten off the ground, with only around 800 officers (mostly from Kenya and the Caribbean) arriving so far.

There are reports that the CPT has turned to private military contractors—some linked to former Blackwater operatives—to conduct drone strikes and covert actions. That raises serious concerns about oversight, accountability, and the risk of harm to civilians. At the same time, communities have started arming themselves. Vigilante killings are on the rise, fueling even more instability.

Aid isn’t reaching those who need it most. Despite the efforts of the World Food Programme, UNICEF, and other humanitarian groups, gang-controlled roads and underfunded operations limit their reach. An estimated 5.6 million Haitians are experiencing acute hunger. Cholera outbreaks strain overstretched hospitals, and nearly half a million children are out of school.

Time is running out. If there’s still a chance to avoid full-scale collapse, it rests on three urgent priorities: 1. a robust, coordinated security deployment—not just symbolic peacekeepers, but real help for Haitian police; 2. large-scale humanitarian assistance delivered by air and sea, bypassing gang-controlled roads; and 3. a Haitian-led political process that results in free, fair elections, without foreign imposition or gang interference.

If none of this happens, Haiti risks becoming a failed state in every sense. Starvation, migration, and the rise of gang-run territories as permanent governments could be the next chapter. The world cannot afford to look away.

India has made significant progress in recent times, particularly in access to running water, sanitation, and related services. How much did it help the state to make a jump in the standard of living of all, especially children, given your experience in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka?

Recent data from the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) indicate that Andhra Pradesh has made steady and meaningful progress in child nutrition and access to clean water and sanitation. Between 2005 and 2021, the prevalence of childhood stunting decreased from 38.4% to 31.4%. That’s significant, given that stunting is a long-term indicator of poor nutrition and living conditions. Underweight rates have also declined, although wasting—a sign of acute malnutrition—remains a concern.

Sanitation improvements have been impressive. In just a few years, access to toilets rose from about 61% in 2015 to nearly 79% by 2021. Clean water availability remains high, at around 91%. Thanks to the Jal Jeevan Mission, tap water connections have skyrocketed from 17% in 2019 to over 73% by 2024.

The Swachh Bharat campaign made a significant difference. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls also improved sharply, with over 85% now using safe products. These basic WASH improvements (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) have saved lives. Child mortality linked to diarrheal diseases and infections has dropped where toilets and clean water became available.

Andhra Pradesh serves as a poignant reminder that targeted policy investments in water, sanitation, and child nutrition can transform lives. But continued effort is needed to reach tribal and remote communities and to ensure these gains are sustained.

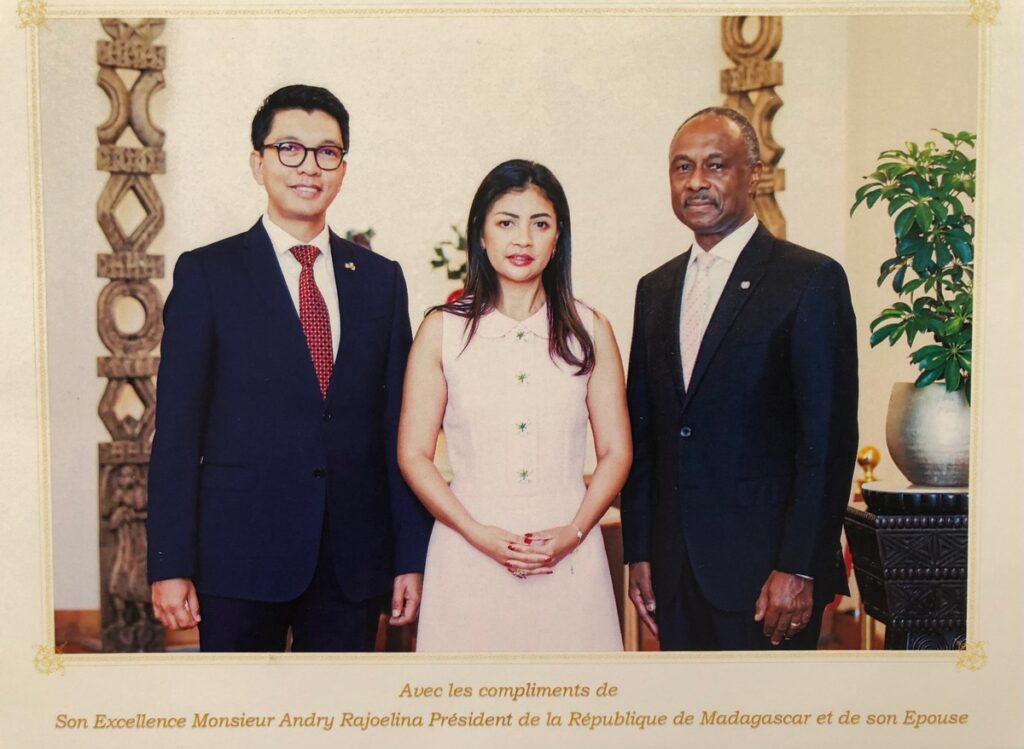

As a former Country Representative in Madagascar, how different is the situation in Madagascar from the main hotspots where help is needed?

Southern Madagascar, especially the Grand Sud and Grand Sud-Est, is in deep crisis. A toxic mix of drought, storms, flooding, and entrenched poverty has pushed millions into food insecurity. Between January and April 2025, nearly 1.94 million people—about 18% of the surveyed population—were in acute food crisis. That’s up from 1.63 million at the end of 2024. Malnutrition among children is especially alarming. In parts of the southeast, repeated cyclones have destroyed crops, homes, and health centres. Severe wasting among children, though improved from a 2022 peak, remains at 6%. Cyclone Jude, which struck in March 2025, displaced thousands and caused widespread damage to infrastructure in the Atsimo-Andrefana and Androy regions.

Post-disaster health care and WASH services are hanging by a thread. Disease outbreaks—diarrhoea, malaria (22.4% prevalence), and respiratory infections—are widespread. At least 20 cyclone-damaged health centres remain non-operational, affecting more than 21,000 children. Education and child protection are also suffering. More than 70,000 children have dropped out of school, while early marriage, child labour, and gender-based violence have increased sharply in many communities.

UNICEF, MSF, Action Against Hunger, WFP, and others are responding with food aid, mobile health teams, clean water projects, and cash support for vulnerable families. But access remains patchy, and climate threats continue. Southern Madagascar is stuck in a cycle of climate disaster and structural vulnerability. Recovery will take more than relief—it needs long-term investment in climate resilience, health, education, and infrastructure.

What, in your opinion, is the biggest problem nowadays? You stated that in many developing countries, access to electricity remains a challenge, particularly in Africa, where 600 million people lack access to electricity, with 98% of them residing in sub-Saharan Africa. Why is the Black Continent so neglected, even though it is, by all accounts, the continent of the future?

Sub-Saharan Africa holds immense promise. It’s the youngest region in the world, rich in natural resources, and home to some of the fastest-growing cities and digital economies. But despite this potential, it remains underrepresented in global economics, politics, and media. Much of this is due to colonial legacies, including unnatural borders, fragile institutions, and economies built around extraction. After independence, many African nations faced corruption, conflict, and underinvestment in people and infrastructure.

Today, global systems continue to disadvantage Africa. Rich nations subsidise their farmers, undercutting African agriculture. Trade deals favour raw material exports, not value-added products. Violence remains a persistent drag, from coups to terrorism to ethnic conflict. Meanwhile, Western media often focus on Africa’s problems, overlooking the innovation, creativity, and resilience that thrive across the continent. Cities like Lagos and Nairobi are booming tech hubs. Mobile money platforms and homegrown solutions, such as M-Pesa, are revolutionising access to finance. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) represents a significant step toward increasing intra-African trade.

But to move forward, Africa needs more than slogans. It requires substantial investment in schools, clean energy, roads, and effective governance, led by Africans and supported by fair global policies. Africa isn’t just the future. It’s a region already rewriting its narrative—if the world listens.

You were a very dear guest and a popular public figure during your time in Serbia. How often do you visit here, and what are your connections to our country these days?

Serbia has become more than a place I once worked—it’s part of my family’s story. From 2013 to 2018, we lived in Belgrade, and we’ve returned almost every year since. Each visit brings back memories, friendships, and a sense of belonging that’s rare.

In 2023, I received the Nikola Tesla Ambassador award from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—a deeply moving honour. During my most recent visit, I had the privilege of donating an audio recording of my grandfather, Émile Saint-Lot, reading the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at the UN in 1948. That recording is now archived in the Museum of Serbian Diplomacy.

We often time our visits with Belgrade’s vibrant Tango Festival, which draws dancers from all over the world. We also take advantage of regular checkups—Serbia’s public health system has always served us well. Serbia has shown us nothing but warmth and hospitality, from bustling cities to quiet villages. Despite early warnings about possible racism, our experience has been the opposite—full of kindness, openness, and friendship. And of course, there are the simple pleasures: long meals in kafanas, biking along Ada, and the unforgettable taste of ajvar and dunja. Serbia isn’t just a memory for us—it’s an ongoing chapter in our lives.

All Photos: Private Archive