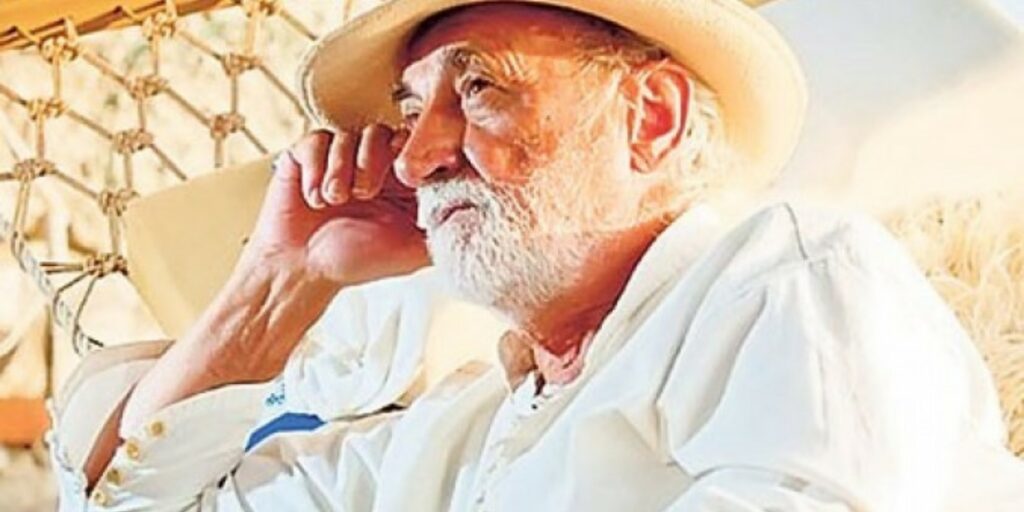

Arsenije Arsa Jovanović

1932 – 2025

In the span of just a few weeks, Serbia lost three towering cultural figures: Arsenije Jovanović, Mirjana Miočinović, and Filip David—lifelong friends and companions of Danilo Kiš, the celebrated Yugoslav writer and intellectual. Their passing marks more than coincidence; it feels like the closing chapter of an era. One could imagine a literary mystery dedicated to them—not to uncover a crime, but to reconstruct a vanished world, a country that no longer exists, and a better past whose demise was long ago prophesied by Kiš’s premature death.

Moreover, considering Arsenije’s eternally boyish character—something of a local Tom Sawyer—his ship’s log, a kind of nautical biography, met a symbolic counterpart in the destruction of the Sava Bridge, beneath which he grew up. That arc of steel, all that remained of the bridge, may well have marked the final, perfect moment for his departure.

Yet Jovanović remains notable also as the penultimate and most renowned Serb of Rovinj—a man who elevated that Istrian town, alongside Belgrade’s Dorćol and Vračar, into a symbolic quarter of Yugoslav urban mythology and popular culture. The last of his generation still living is his contemporary, the celebrated ex-Yugoslav writer and current Berlin resident, Bora Ćosić. In his elegiac essay Peaceful Days in Rovinj, Ćosić writes: “Arsenije has sat at this table for decades, yet I’ve never quite been able to define him—something always slips away, something is still missing.”

A bundle of answers lies in Jovanović’s memoir, the so-called Dishevelled Biography. Impossible to summarise, it is, in essence, the chronicle of an analogue era—somewhere between Melville’s Moby-Dick and Kerouac’s On the Road—a world we can only admire and envy. As a boy, he journeyed upriver in a makeshift boat, tagging along with tugboats to Sisak, and then paddled down the Sava back to Belgrade. In the next chapter of his life, he sailed the Danube, across the Black Sea and Mediterranean, until he reached Rovinj, where he dropped anchor for good.

In a famous 1990s interview with Slavko Ćuruvija, Jovanović remarked that the controversial SANU Memorandum had been written in the Batana tavern in Rovinj. Although he taught at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, he left the institution in the early 1990s. From his theatrical beginnings in Zadar and Šibenik, and later at the National Theatre in Belgrade, he became one of the most respected directors at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (JDP), particularly in collaboration with Boro Mijač. Their adaptations of Dobrica Ćosić’s works—The Battle of Kolubara and The Valjevo Hospital—would come to represent patriotic zeal, only to eventually deconstruct it.

This was also the era of Jovanović’s life in New York, where he lived at the legendary Chelsea Hotel alongside eccentric Russian artists, Dragan Babić, Liv Ullmann, and the ever-present Danilo Kiš.

From that decade of creative expansion emerged his outstanding television work—intimate dramas and two-part legal series. It took another half-century and Christopher Nolan’s global spotlight on Robert Oppenheimer for RTS to remember that Jovanović had already made a docudrama about the physicist in 1970, starring Branko Pleša. He would go on to produce similar works: Lee Harvey Oswald, The Trial of Flaubert, The Sarajevo Assassination, The Burning of the Reichstag, and Why Did Alija Alijagić Fire the Shot?

For anyone exploring Serbia’s political history and cultural anthropology, two of his dramas are essential: The 67th Assembly of the Principality of Serbia (1977) and The First Serbian Railway (1979), both dissecting the themes of state support for culture (e.g., the National Theatre) and corruption (e.g., the bankruptcy of a French investor).

Though a visionary and pioneer, Jovanović spent the 1980s making the documentary series Time of Frescoes. That spiritual exploration would eventually turn him toward a new medium—ambient sound as a form of cinematic composition. From water gurgling and waves crashing, to birdsong, animal calls, the rhythm of cities, church bells and traffic—his edited soundscapes would ultimately find their way into the audio palette of Hans Zimmer, in Terrence Malick’s Oscar-winning The Thin Red Line.

In the 1990s, Jovanović became both friend and mentor to the celebrated American director. It was also the decade in which he fought to preserve his own home in Rovinj—so it wouldn’t share the fate of Radomir Konstantinović’s house. Rovinj became a kind of intellectual exile, sheltering Mirko Kovač, Bora Ćosić, and Jovanović himself. Together, they maintained their moral and intellectual integrity in this liminal space, reached by train and bus via Budapest, Vienna and Trieste, as war consumed Yugoslavia and its final drama unfolded on the Serbian-Croatian front.

Zlatko Crnogorac