Camino means “the way” in Spanish, and the adventure of the Camino de Santiago is exactly that – a journey of the soul

TRAVELOGUE

by Lidija Ćulibrk

It is a challenge that strips you of distractions, confronts you with yourself, and invites you to walk in peace, take stock of your life, and make new decisions. It is, quite literally, a path.

The real Camino for me happened long before I set foot on the trail – in my bed, in my head

When people ask me if it was hard or whether I ever thought of quitting, I realise that the real Camino for me happened long before I set foot on the trail. It was in my city, in my bed, in my own head – a hellish storm of thoughts, dilemmas, doubts, and attempts to prevent problems I imagined were waiting for me. I knew the challenge was immense, and I refused to give up after just a few sleepless nights or a bout of aching muscles.

At the end of last year, I decided that the coming year would see me spending far more time in nature, no matter the weather. One winter’s walk through Fruška Gora, I heard a woman I didn’t know say to me, “You should go on the Camino this year…” I am not one to trust voices from nowhere, meant only for me, but as I crunched through the fresh snow, I felt the blaze of the Spanish sun and a summer that was still months away. I thought: “What an adventure that would be… and why not…” And just like that – not at all like me – I decided without a second thought: “I’m going! To see what I am truly capable of…” Yes, my joints ache, I struggle with sleep, and I am not exactly in peak condition.

Camino is a story of anti-comfort – proof of how little we truly need

That was my thinking until summer finally came, bringing with it suffocating June heat and scorching days when even night brought no cool relief. Suddenly, I doubted whether I could master even the challenge of sleeping in my own air-conditioned flat, let alone a night in dormitories with twenty or thirty beds. Still, I kept paying the instalments for the trip, and soon it was time to start packing – or in my case, to acquire the gear I had never owned.

My daughter gave me a copy of Marina Juranić’s Confession on the Road to Santiago, and the further I read, the braver I felt. The journey began to take on a tangible form. I gathered a borrowed backpack, a headlamp, a power bank, and oversized noise-cancelling headphones meant to shield me from dormitory noise. I treated my feet to brand-new Salomon trekking shoes, packed a sleeping bag, woollen socks and underwear that promised to keep me calm. I stocked up on vitamins to keep me healthy, electrolytes, and Compeed blister plasters for the road, and sleeping pills that, alongside earplugs, an eye mask, and lavender oil, were my only hope of rest.

Ten days before departure, I walked 30 kilometres for the first time in my life – as much as we would need to cover on the longest days of the trek – to see how it felt, aware that I was a recreational walker rather than a serious trekker. A few days later, I hiked with a packed rucksack – as it turned out, much lighter than it would be when weighed at the airport before flying to Porto. I even treated myself to a few massages to relax my muscles and, in the end, I felt I had done everything I could to prepare. And I should not forget – alongside my family, who supported me wholeheartedly, there was ChatGPT, constantly encouraging me and repeating: “Focus only on this one day, this one step, on what you see in front of you…” I loved its mindful approach, and I often turned to it.

Every stone beneath your feet reminds you that freedom is not given but earned

The starting point of our “Portuguese route” was the beautiful cathedral in Porto, where we received our pilgrim’s passport and the scallop shell that now hangs on my wall – the unmistakable symbol of those walking to Santiago de Compostela. The passport is essential, as it is stamped at every stop along the way, providing a true record of your journey. Beyond being a cherished keepsake, it also serves a practical purpose in the albergue, the pilgrim accommodation, as proof that you are indeed walking the route and not just passing through as a tourist.

Whether we were truly pilgrims or merely tourists is hard to say. We were a group of nineteen, led by Ljubica Selaković Bandić and Žarko Atanasovski, now at the helm of the “Montanika” mountaineering club, and none of us were pilgrims in the traditional sense of the word. We wanted to walk, to be in nature, to claim a little space for our thoughts. Perhaps that is enough. Yet, the one who first carved out this path might not agree.

Camino is life in motion – silence, struggle, and the opening of your heart

St James was an early Christian who, in the year 44, came to the Iberian Peninsula to spread the teachings of Christ. Preaching love for one’s neighbour and forgiveness, he travelled as far as Finisterre – whose name itself means “the end of the world” as it was known to medieval people (and where we too would eventually arrive, though with the help of modern transport, since the end of our route was Santiago de Compostela). After his martyrdom in Jerusalem, the remains of the apostle were brought back to Spain by his companions and buried where Santiago stands today. For centuries, his bones lay hidden until one night in the ninth century, thousands of stars appeared to light up the sky above them, spotted by a shepherd. A small chapel was built on that spot, growing larger over the years until it became the monumental cathedral that can be compared today only with St. Peter’s Square in Rome.

Legend has it that the king who recognised the significance of this vision became the first pilgrim to the new shrine. After the first church was built in 829, a new pre-Romanesque one was constructed in 899 by order of King Alfonso III of Asturias, and the settlement slowly grew into a major centre of pilgrimage.

In 997, the early church was reduced to ashes by Al-Mansur ibn Abi Amir (938–1002), the military commander of the Caliphate of Córdoba. The doors and bells, carried by Christian captives, were taken to Córdoba and placed in the Great Mosque of Córdoba. Construction of the current cathedral began in 1075 under King Alfonso VI of Castile (1040–1109) and under the patronage of Bishop Diego Peláez. It was built to the same plan as the brick-built Basilica of St Sernin in Toulouse – likely the largest Romanesque building in France – but made mostly of granite. Work was interrupted several times, and the final stone was laid in 1122; however, the cathedral was not completed. It was consecrated in 1128 in the presence of King Alfonso IX of León.

It is believed that the cathedral is the work of Master Bernard the Elder and his assistant Robertus Galperinus, and possibly later Esteban, who worked on the cathedral’s final phases. Bernard the Younger completed the last stage, while Galperinus coordinated the work and built the monumental fountain in front of the north portal in 1122.

The church became the seat of a bishop, and its growing importance as a pilgrimage centre led Pope Urban II to raise it to the status of an archbishopric in 1100. A university was added in 1495. The cathedral continued to be decorated and expanded between the 16th and 18th centuries. After that, pilgrimage declined during the Enlightenment, only to be revived in the 1980s, in an era that promoted walking, physical activity, and healthy living.

Encountering the square full of pilgrims and walkers who had arrived before us was truly moving. Even if you are not deeply religious, the space forces you to face yourself, to confront what you carry within you and what you have wrestled with on the road leading to the cathedral. What disturbs such a sacred moment, however, is the modern urge to capture every instant of life through photos and videos, prioritising the recording of the moment over actually living it. I had hoped to have time later, once I had separated from the group, to reflect on my own – and I did. That same afternoon and the next morning, I sat with my rucksack and thought about myself, stronger and more capable than I usually believe myself to be.

“This Camino is not just a path – it is a mirror of life, with all its burdens, doubts, and moments when strength falters and the soul needs a reason to keep going. Every stone beneath your feet reminds you that freedom is not given but earned,” said our guide Ljubica. She was right. She was also right when she told us we would deal with problems as they came and that there was no need to wrestle with them too far in advance. This was an important lesson for me, as I tend to pour far too much energy into preventing problems and overthinking situations that may never actually happen. And it is true – almost unbelievably so – that it is much easier to face problems when they actually arrive than to battle them as shapeless fears hanging over you, causing needless anxiety.

On this journey, for example, I was terrified of bedbugs. I spent so much time thinking about them, reading about them, figuring out which repellents were most effective, how to find them, and how to apply them safely without poisoning myself. Pilgrim hostels are very busy, allowing guests to stay only one night (because they are meant for walkers, not those taking a rest day), and by their very nature, they are low-cost – around fifteen euros per night – which makes them difficult to keep spotless. Bedbug stories circulate constantly. Pilgrims resort to every possible trick: spraying their rucksacks and sleeping bags with special insecticide (not available in my country), carrying anti-bug liners, or putting their faith – wrongly – in herbs. I ended up doing just that, rubbing lavender oil on myself before bed. And yet, one morning at first light, I discovered I was covered in bites. Still, I kept walking. I grumbled a little, treated the bites with creams, and took two antihistamines; the angry red marks began to fade. One of the situations I had feared most had come to pass – and somehow I got through it, or perhaps it resolved itself. Back home, that fear had been so intense that, had I known it would really happen, I might have given up the whole idea; it was almost on par with my dread of sleeping in large dormitories.

I am the sort of person who happily pays extra for a single room, however expensive, to have privacy and comfort. Camino, by contrast, is a story of anti-comfort – a reminder of how little we truly need. The realisation that you can survive seventeen days in dormitories and shared bathrooms, arranging shower times together, washing and drying clothes with others, repacking excess gear into shared bags – takes you back to the communal life of early human society. And admit it, we all sometimes wonder what that might have felt like. And I must admit – it feels good. The feeling that I can not only sleep in a dormitory but rejoice at finding a socket and a tiny reading light next to my bed. That I can live with just two pairs of underwear, yet always be clean because I wash and dry one pair the moment I arrive at the hostel. The discovery that I can survive without “all those things” is minimalism in its purest form, proof that we have all burdened ourselves with too many supposed necessities and dread situations where we might have to go without them. My Camino experience taught me that you can get by with almost nothing. The one civilised habit I never abandoned was my morning coffee – often prepared with lukewarm tap water or even under the shower – which I would carry with me at dawn as we set off for the next destination.

Now, while I am still in my post-Camino blues, I keep thinking about – as Jasmina so beautifully put it – the daily nomadic rhythm of our ancestors, moving from one shelter to the next, for whom the very act of finding a new place to stay was the sole goal and ultimate source of dopamine.

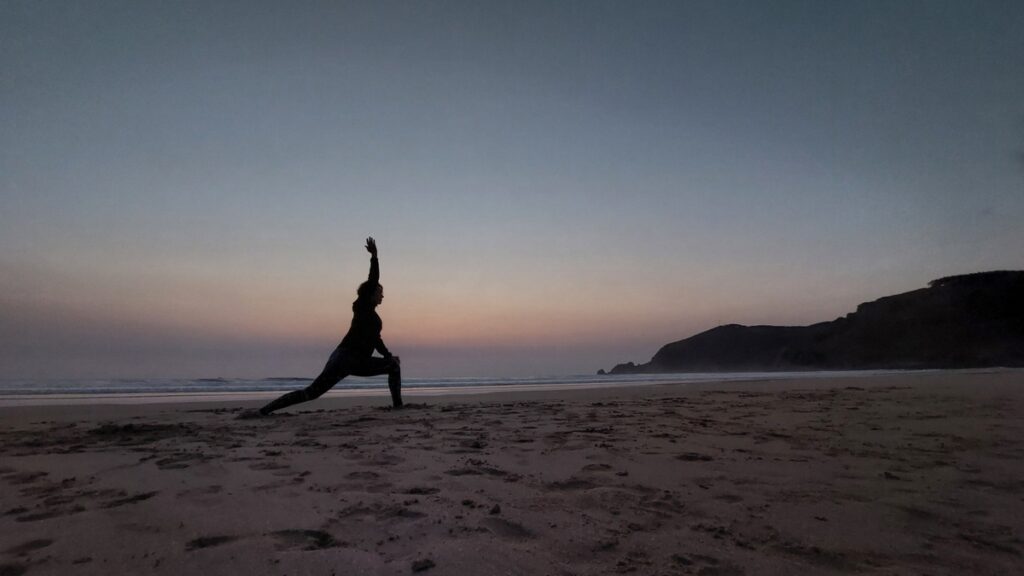

And then there was the second extraordinary gift – the nature we walked through. In Portugal, we strolled along the ocean shore, almost always on flat paths, often on boardwalks edged with ropes. The ocean foamed in the distance, crashing against the rocks, with salt and sand floating in the air. Dawn took its time to arrive, and the early wake-up calls and departures in the dark carried their own magic. I rarely get up that early, so watching the world as it woke and, it seemed, came into being again was a blessing. The small towns we passed through were still cloaked in darkness and felt like they belonged only to us. Roosters crowed as we crossed farmland, and every tree and blade of grass was wrapped in stillness. These images are perhaps the first that come to mind when I think of the Camino. When we crossed into Spain, we were greeted by the rolling hills of Galicia, featuring its beautiful and vibrant landscapes and charming villages.

The route was exceptionally well-marked, so we could not have lost our way even if we had walked alone, as most people do. Apart from ours, the only groups of pilgrims we encountered were Italian, just as cheerfully noisy as we were. When the kilometres to the destination dropped below one hundred, people would often pose for photos next to the stone markers that matched their age. Our guides had walked the entire French Way in 2023, leading the first Serbian group to complete this long route. The French route is classic, crowded, full of people, small monasteries, and history, offering a deep sense of shared tradition. Our Portuguese route, being much shorter, was more intimate, quieter, and featured more natural and coastal scenery. It gave us the feeling of a personal journey, of freedom and of setting our own pace.

“Camino is not tourism or a holiday… it is more than a route. It is life in motion – the silence and noise of your own thoughts, the struggle with fatigue, with blisters, with the limits of your body… but also the opening of your heart, the unexpected friendships, the sense of freedom. Camino demands sacrifice and patience, but in return, it gives you inner peace and a strength that is hard to put into words. Tiredness comes, but so does the joy of knowing that each day brings us closer to the goal – both the outward one and the one within. No one is truly tired – we are all moving towards the finish!” Ljubica and Žarko would remind us. They were aware of something I had not fully realised – that perhaps the greatest challenge of such a journey is finding your place within the group and learning to live with eighteen strangers with whom, in many moments, you share deeply personal experiences.

And now, as I think about the next challenge and the next journey, the small, picturesque towns pass before my mind’s eye – La Gruge, Agucaudora, Caminho, Marinhas, Viana do Castelo, Mougás, Baiona, Vigo, Redondela, Pontevedra, Caldas, Padrón, and Santiago de Compostela – and I can’t help but think: why not again? There are so many routes leading to Santiago – why not try at least one more!